THOMAS HAUSER

Henry Armstrong Revisited

THE SCORECARD / HENRY ARMSTRONG REVISITED

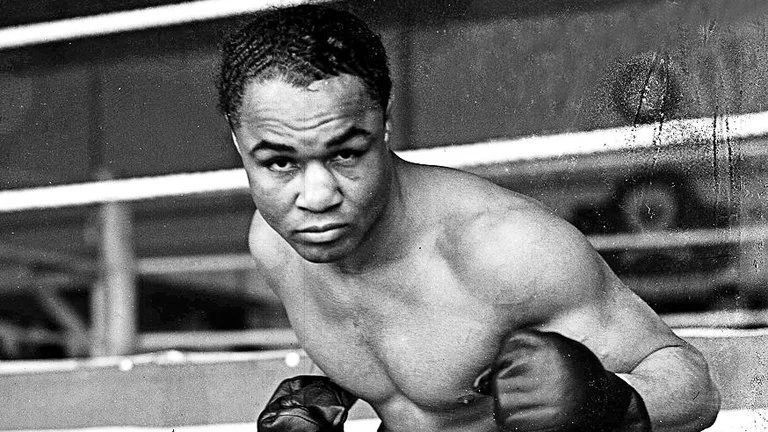

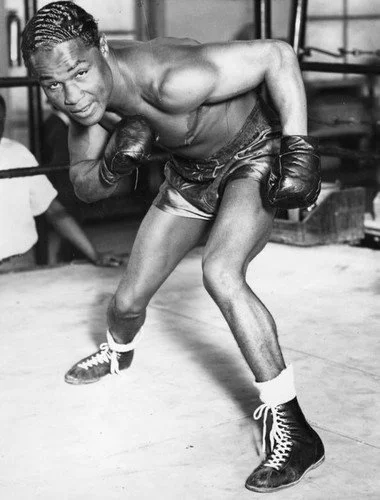

Henry Armstrong is largely forgotten today, overshadowed by memories of Joe Louis and Sugar Ray Robinson. Some boxing fans have seen bits and pieces of him on film. A barrel-chested fire-plug of a man, five-feet-five-and-a-half inches tall with an irrepressible smile; always moving, like a kid in a playground with a seemingly inexhaustible supply of energy.

Boxing fans also know that Armstrong won multiple titles. But in recent decades, the concept of a “world champion” has been watered down. So let’s put what he did in perspective.

Armstrong fought twenty-seven fights in 1937 and won all of them, twenty-six by knockout. He captured the featherweight crown that year by knocking out Petey Sarron. Then, over the next nine months, he added the welterweight championship with a lopsided decision over Barney Ross and annexed the lightweight title with a victory over Lew Ambers. For good measure, he fought twelve title fights in 1939 and won eleven of them.

Armstrong held three world championships simultaneously at a time when boxing had eight weight divisions and only one champion in each division. He was "pound-for-pound" before the phrase was invented for Sugar Ray Robinson. His accomplishments were almost beyond comprehension.

The details of Armstrong’s early life are shrouded in uncertainty. He gave different versions of events to different people. The Ring Record Book says that he was born in Columbus, Mississippi, on December 12, 1912. That conforms with his public statements. But British writer Bob Mee (who studied the census rolls in Lowndes County) argues persuasively that his actual date of birth was December 12, 1909.

Armstrong was the eleventh of fifteen children born to Henry and America Jackson. His mother was an Iroquois Indian. His father was black with some Indian and Irish blood mixed in. At birth, he was given his father’s name; Henry Jackson Jr.

The Jacksons were a sharecropping family. They grew cotton. Then boll weevils descended on the cotton fields, and Henry Sr went north to St. Louis with his two oldest sons (Oilus and Oscar). They found factory jobs and, when they’d saved enough money, the rest of the family joined them in a three-room house on the rough-and-tumble south side of the city.

America Jackson died young. “My mother was strong,” Henry recalled years later. “But having all those kids; you’re just human. She’d have a kid today and start working almost tomorrow. She just worked herself down and caught what you call consumption of the lungs.”

Henry’s paternal grandmother took his mother’s place in the life of the family. At her urging, he continued his education and graduated from Vashon High School. Then he took a job as a laborer for the Missouri Pacific Railroad at a salary of twenty dollars a week. After six months, he was laid off. He later claimed that, while working for the railroad, he read in a St. Louis newspaper that Kid Chocolate (then undefeated in forty-two professional fights) had beaten Al Singer at the Polo Grounds in New York and been paid a purse of $75,000.

Jackson was impressed with Kid Chocolate’s earning power. In due course, he landed another job; this one at the Universal Hat Shop, where he cleaned and blocked hats and made deliveries. He also decided to try his hand at boxing and learned some fundamentals at the “colored” YMCA on Pine Street in St. Louis. At the YMCA, he met an older fighter named Harry Armstrong, who watched him spar and offered the opinion, “You’re a good fighter but no boxer. You can’t be good just by being willing to hit and be hit. A boxer doesn’t take hits. He slips them and the other guy gets hit.”

With guidance from Armstrong, Henry Jackson had three amateur fights in St. Louis and won them all by knockout. Then they journeyed to Pittsburgh to try their hand in the professional ranks. At that point, Armstrong decided that Henry needed a catchier name and dubbed him “Melody Jackson.”

On July 27, 1931, Jackson made his professional debut against Al Iovino in North Braddock, Pennsylvania. His purse was thirty-five dollars. The next day’s edition of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette told the tale.

"Al Iovino, Swissvale, 123 pounds, knocked out Melody Jackson, recent importation from the South, in the third round with two minutes and 27 seconds of the session gone. Jackson started out trading wallops and kept it up until he grew tired with both lads slugging toe-to-toe. Iovino got Melody in bad condition as round three progressed, the southern lad showing extreme dislike for body blows. When Al clipped him with a long overhand left that found its target, Jackson went face down upon the canvas."

Four days later, Jackson had his second pro fight and won a six-round decision in Millville, Pennsylvania. But the fight was tougher and the purse was smaller than he and Armstrong had thought they would be. They returned to St. Louis. Then, in pursuit of more lucrative opportunities, they rode on the underside of trains to California, stopping in hobo camps for rest and food along the way. The trip took eleven days.

Jackson and Armstrong spent their first few nights in California with other drifters and homeless people at the Midnight Mission in Los Angeles. Eventually, they rented a partitioned area with a single bed between the laundry room and back yard of a house for a dollar a week.

At that time, amateur boxing in California was a semi-professional sport. Jackson soon signed a contract to fight as an amateur under the guidance of a manager named Tom Cox. But there was a problem. He’d fought twice professionally in Pennsylvania.

At Harry Armstrong’s suggestion, Henry Jackson became Harry’s little brother, Henry Armstrong. That was the name on the contract that he signed with Cox. The fighter later claimed that, during his first year as an amateur in Los Angeles, he had between eighty-five and ninety fights and won all of them. A more plausible accounting is that he won 58 of 62 amateur fights, earning a few dollars on the side for each fight. He shined shoes to make ends meet.

In summer 1932, “Henry Armstrong” competed for a spot on the United States Olympic Team but was eliminated in the trials. At that point, Cox sold his contract to Wirt Ross, a manager with connections in the pro game. Henry Armstrong approved the assignment and extended the terms of the contract so that it would last for five years. That bit of business taken care of, he turned pro with Harry Armstrong as his trainer and lost four-round decisions in his next two fights. Each time, he was overmatched. Basically, he was exciting cannon fodder. But he made fifty dollars for each fight.

Henry Armstrong now had one win and three losses in four pro fights. But he was learning how to harness his natural physical gifts; strength, quickness, stamina, and the ability to take a punch. In the two years after his first four fights, he fought thirty times and lost only once. At one point during that stretch, he had five draws in six fights; a testament to judging that was biased against him. But he was fighting in an era when blemishes were an expected part a fighter’s record and didn’t doom his future.

In November 1934, Wirt Ross sent Armstrong to Mexico City to fight Mexican native Baby Arizmendi (a world-class featherweight) for a purse of $1,500. Years later, in an autobiography entitled Gloves, Glory, and God, Henry maintained that, just before the fight, Ross told him, “Don’t get too ambitious, son. You’re not supposed to win this fight.”

Armstrong responded, “I thought I’m supposed to win all my fights,” and Ross explained the facts of life to him.

“You’re a good boy, but there’s a lot you’ve got to learn about the fight game. I want you to take it easy in this fight. I gave my word that we’d fight this one the way Arizmendi’s manager wanted it. It was the only way I could get you signed. Just fight to go the full ten rounds.”

Arizmendi won a unanimous decision. Afterward, Ross told Armstrong that he wouldn’t be paid because the gate receipts had been stolen.

In 1936, Ross sold Armstrong’s contract to Eddie Mead for $10,000. Hollywood stars Al Jolson and George Raft were partners in the purchase. Later that year, Henry moved up to lightweight. By autumn 1937, he had 72 victories on his ring record.

On October 29, 1937, Armstrong returned to the featherweight division and challenged Petey Sarron for the 126-pound crown at Madison Square Garden. Making weight was a struggle; but on the morning of the fight, he weighed in at 124 pounds. Later that day, relaxing in bed, he drew parallels in his mind between what he hoped to accomplish in boxing and the exploits of George Dixon, Joe Gans, and Kid Chocolate; three great black champions who had come before him.

In the dressing room before the fight, Eddie Mead told Armstrong, “Sarron isn’t such a hot puncher. Just walk in, throwing punches hard till you give him the punch it takes to put him out.”

Harry Armstrong (who was Henry’s chief second) later recalled that both fighters “fought savagely” that night and “threw caution to the winds.”

Joseph Nichols summed up the bout for the New York Times, writing, “Sarron clearly won the first four rounds of the sizzling battle by eagerly inviting Armstrong’s attack and cleanly beating the Negro in counters. Neither fighter paid heed to the so-called finer points of boxing. They merely rushed at each other time and again, both arms swinging, and the encounter was one long succession of thrilling exchanges to the head and body. When the sixth round started, Armstrong sprang at his adversary and drove both hands to the body. One punch, a heavy right, apparently robbed Sarron of all his strength, for he was able to do nothing except cover up while Armstrong belabored relentlessly with lefts and rights to the mid-section. Recovering somewhat, Sarron jumped at Armstrong and traded willingly with him until the latter, releasing his long right, crashed it squarely against Sarron’s jaw. Sarron slumped to his knees and elbows and slowly lifted himself.”

But the beaten champion was in no condition to continue. Referee Arthur Donovan stopped the battle at 2:36 of the sixth round.

That night, there was a victory party at the Cotton Club in Harlem. Armstrong said later that he felt like “a giant firefly in a blackout” and recalled that celebrities who wouldn’t have given him a glance in passing a few days earlier greeted him “like a long-lost relative.”

There hadn’t been many African-American champions before Armstrong. Joe Gans, Jack Johnson, Tiger Flowers, and Joe Louis (who preceded Armstrong by four months) were the most notable. Major League Baseball and the National Football League were still all-white institutions. “Boxing,” W.C. Heinz later noted, “gave the black man a better break than he received in any other sport because it needed him. But it only gave him what it had to.”

That said; Armstrong fought in a manner that demanded attention.

“I look at films of the oldtime fighters a lot,” says Emanuel Steward. “Henry Armstrong is the first boxer I ever saw who was like a machine. It wasn’t combinations as much as it was punches coming all the time. Nobody could throw that many punches, but he did. He had incredible stamina and was absolutely non-stop. He was a perpetual-motion punching machine. When the bell rang, he got in your face and started throwing punches from every angle. He was like a machine gun. It wasn’t bang! It was bang-bang-bang-bang-bang-bang! Nothing stopped him. He just kept coming and coming and punching like a windmill in a hurricane. He was born with natural gifts that allowed him to fight the way he did. There was no way to get away from him and no way to tie him up. When you fought Henry Armstrong, you were fighting for your life every second of the fight. A lot of his defense was in his offense. He never slowed down. But if you look at the films closely, you see all the subtle things he did. He could take a punch, but he also kept his chin close to his chest, so you couldn’t hit him cleanly. He had a way of getting his elbows back against his body so, when he got inside, the opponent couldn’t tie him up. His arms never got out to where you could clinch with him. That’s what enabled him to be perpetual motion and grind people down with that relentless suffocating attack of his for fifteen rounds.”

“There had never been a fighter like him before,” adds Don Turner. “In the ring, he was pressure pressure pressure. Perpetual motion, throwing punches all the time from all angles; bobbing and weaving so the other guy couldn’t land a good shot. He never took a step back. You had to fight his fight because he gave you no choice. And you had to punch with him because he never stopped punching. He just wanted to fight. He overwhelmed his opponents. In boxing, very often, the mind carries the body. Henry Armstrong made every sacrifice that a fighter has to make to be great. His will to win superceded everything.”

Armstrong fought seven times in the twelve weeks after he defeated Sarron; all of them knockout victories in non-title fights. Then, in late-January 1938 while driving home to California, he suffered what he referred to in his autobiography as “a nervous breakdown.” He was taken to a “ranch” in Fontana, California, where he recuperated for a week.

Two days after his release, Armstrong was back in the ring. He fought four times in February 1938 and three times in March; each time as a lightweight, winning all seven fights. The seven men he defeated (Chalky Wright and Baby Arizmendi among them) had 445 victories at the time he fought them. He’d now won 37 consecutive fights, 35 of them by knockout, and was referred to in the nation’s press as “Hammering Hank . . . Homicide Hank . . . Hurricane Hank . . . The Human Buzz-Saw . . . The Human Dynamo.”

Then Armstrong attempted the unthinkable.

“Joe Louis had just won the heavyweight championship,” Armstrong later recalled. “He was going to take all the popularity, everything, away from all the [black] fighters because everyone was saving their money to see Joe Louis. I had three managers; George Raft, Al Jolson, and Eddie Mead. They came up with the idea that I had to get super-popular, colossal. They said, ‘We want you to win three championships. We worked this out because we were trying to make more money. They said, ‘If you can win three championships, you’ll have the flamboyance of a heavyweight. These guys were the thinkers. I said, ‘It sounds pretty good to me. Okay; get ‘em together.’”

Only one man prior to Armstrong (Bob Fitzsimmons) had won championships in three weight divisions. And Fitzsimmons accomplished the feat over the course of twelve years. Armstrong had something far more audacious in mind. He hoped to hold the featherweight, lightweight, and welterweight titles at the same time.

Armstrong’s management team wanted him to fight lightweight champion Lew Ambers after beating Sarron and then go after welterweight champion Barney Ross. But Al Weill (who managed Ambers) was resistant to the idea, so Armstrong challenged Ross first.

Ross (named Beryl David Rosofsky at birth) was from New York and was known as “The Pride of the Ghetto.” He’d won the lightweight title by beating Tony Canzoneri in 1933 and seized the welterweight crown from Jimmy McLarnin two years later.

Ross-Armstrong was scheduled for May 26, 1938, at the outdoor Madison Square Garden Bowl in Long Island City. It would be the first time in boxing history that a reigning featherweight champion had challenged for the welterweight crown.

Rain caused a five-day postponement.

Despite the 147-pound division limit, Ross weighed in at 142 pounds; Armstrong, at 133-1/2.

Ross was a 2-to-1 favorite. But he was well past his prime. He won the first few rounds by outboxing Armstrong and controlling the fight with his jab. Then he faltered. Cornerman Art Winch (also Ross’s co-manager) asked his fighter, “You started so nice. What’s wrong, Barney?”

Soon, everything was wrong.

Ross, in his own autobiography, later described the pivotal middle rounds as follows.

Round six: “Something happened to my legs. I couldn’t seem to move on them. My arms felt as if they had lead weights on them. It was all I could do to get them up to protect my face, let alone fight back.”

Round seven: “I was puffing badly, starting to wheeze. I fought for breath. I was lucky to get out of the round alive.”

Round eight: “He rained left hooks on my mouth and blood gushed out. He hit me in the eye and it closed tight. Another punch cut my lip open. Another crashed into my nose, starting another flow of blood. Blood was dribbling into my good eye, so I was practically blind. I was taking such a beating to the stomach, I wanted to throw up right in the middle of the ring.”

Writing for the New York Times, James P. Dawson called the fight “fifteen rounds of vicious savage fighting that was so onesided as to render the result a foregone conclusion midway in the battle.”

“Like a human tornado,” Dawson recounted, “Armstrong cut down Ross. There was no resisting force. Henry just pounded the gallant Ross tirelessly, pitilessly, through every one of the fifteen rounds. Armstrong demonstrated almost from the opening bell that his style, his strength, his inexhaustible supply of stamina, perseverance, his grim determination, in short, his singular fighting stock in trade were too much for Ross.”

Ross never went down. He made it to the final bell, barely, on courage alone. His eyes were slits. He was bleeding from the nose and mouth. He was beaten to a pulp but refused to quit, begging his corner and referee Arthur Donovan for the right to continue until the very end.

“A champ’s got the right to choose the way he goes out,” Ross said when the carnage was done.

Armstrong later claimed that he carried Ross the final three rounds out of respect for the champion. Maybe he did; maybe he didn’t. There’s no corroborating evidence to support or rebut that claim. Either way; he won a lopsided unanimous decision.

“This is your night,” Ross told his conqueror at the final bell. “I’ve had mine.”

In his dressing room after the fight, the beaten champion told reporters, “He’s a great fighter, who never rests and never gives you a chance to rest. I can’t say he’s a hard one-punch hitter, but he certainly can wear you down. I wish I could have fought him five years ago. I was at my peak then. There was something missing in me tonight.” Then Ross said wistfully, “That was my last fight. I wasn’t going to go out lying down.”

Unlike many beaten fighters, Ross was true to his word. He never fought again.

Twenty-two days after Armstrong beat Barney Ross, Joe Louis fought Max Schmeling at Yankee Stadium and annihilated his German foe in one round. The Brown Bomber was now America’s hero. Nothing that Armstrong did could match the exploits of his fellow champion. But there was still a third championship to pursue.

On August 17, 1938, Armstrong challenged Lew Ambers at Madison Square Garden for the lightweight crown. It was one of the bloodiest, most brutal slugfests of modern times. James P. Dawson called the action “fifteen rounds of fighting as fast, furious, and savage as has ever been seen.”

In round three, Ambers opened a cut on the inside of Armstrong’s lower lip that bled profusely for twelve rounds. Then Ambers was knocked down and badly hurt in the fifth and sixth rounds.

As the fight progressed, Armstrong took control on a primitive level. But another factor was at work.

Armstrong wasn’t a dirty fighter, but he was a physical fighter. With his perpetual motion style, he threw punches from all angles and some of them went low. Coming straight forward, he also led with his head from time to time.

Referee Bill Cavanagh took four rounds away from Armstrong for low blows.

By the late rounds, Armstrong was severely cut around both eyes and blood was streaming from his mouth. Cavanagh warned that the blood was making the canvas slippery and that he was on the verge of stopping the fight.

“Don’t stop it, Mr. Cavanagh,” Armstrong begged. “I’m leading on points.”

“The ring is full of blood,” the referee countered. “And it’s your blood.”

“Then I’ll stop bleeding.”

After the twelfth round, Armstrong told his corner, “Don’t give me no mouthpiece. Just let me go.”

He fought the last three rounds swallowing his own blood so Cavanaugh wouldn’t stop the bout. Twelve stitches were needed to close the cut on the inside of his mouth.

Factoring the four penalized rounds into the scoring, one judge scored the bout eight rounds to seven in favor of Ambers. The other two scorecards read 8-6-1 and 7-6-2 for the new lightweight champion and first-ever simultaneous triple champion of the world.

After Armstrong beat Ambers, he relinquished his featherweight crown. He knew that he would be unable to make 126 pounds again. Over the next nine months, he successfully defended the welterweight title six times and had one non-title bout. On August 22, 1939, he put his lightweight championship on the line in a rematch against Ambers at Yankee Stadium.

Again, it was a thrilling fight. Armstrong suffered a terrible cut above his right eye that obscured his vision. And again, he was severely penalized for low blows.

Afterward, James P. Dawson wrote, “Applying the law more severely than ever before and certainly more painfully than it ever has been applied in a championship bout, referee Arthur Donovan penalized Armstrong five rounds [two, five, seven, nine, and eleven] for low blows.”

Ambers won a unanimous 8-7, 8-7, 11-3-1 decision.

“The title,” Dawson noted, “was not won on competition alone, but on fighting rules and ethics. Four of these [penalized] rounds, Armstrong won on competition without a doubt. On this observer's scoresheet, Armstrong was the victim of an injustice."

The loss broke a string of forty-six consecutive victories for Armstrong.

In October 1939, two months after his loss to Ambers, Armstrong defended his welterweight championship five times in twenty-one days. That’s not a typographical error. Three more successful defenses followed.

Then, on March 1, 1940, weighing 142 pounds, he moved up in weight yet again and challenged Ceferino Garcia for the middleweight title. The consensus at ringside was that Armstrong deserved the decision. The bout was declared a draw.

Returning to welterweight, Armstrong scored knockouts in five more title defenses over a five-month period. On October 4, 1940, he put his championship on the line against Fritzie Zivic at Madison Square Garden.

Zivic was a dirty fighter, adept at thumbing opponents in the eye and doing whatever else he could get away with outside the rules. “I’d give ‘em the head, choke ‘em, hit ‘em in the balls.” he said when his career was over. “You’re fighting. You’re not playing the piano.”

It’s now believed that Armstrong was virtually blind in his left eye before he fought Zivic. By the middle rounds, his right eye was swollen to the point where he could hardly see at all. The bout was even on two of three scorecards going into the fifteenth round. Zivic dominated the final stanza.

Joseph Nichols wrote in the New York Times, “Fritzie Zivic did what the rank and file of boxing followers deemed impossible at Madison Square Garden last night. He crushed the heretofore invincible Henry Armstrong into decisive defeat in a savage fifteen-round struggle. Pacing himself splendidly and standing up under Armstrong’s hardest punches, the durable Zivic made his way to the championship by exhibiting a willingness to trade with his foe when expedient and to stay away and stab effectively with a long left hand when that course appeared the better one to pursue. The steady impact of the clever Zivic’s sharp left to the face gradually caused a swelling about Armstrong’s eyes. The tenth round was the one in which every spectator in the house went delirious. The boxers stood toe to toe and each fired his heaviest artillery. In the eleventh round, the defending titleholder was blind to all intents and purposes. Zivic, aware of his foe’s plight, kept the battle at long range and ripped both hands to the head at every opportunity. The pitifully handicapped Armstrong had trouble even locating his tormentor. As he returned to his corner at the end of each round, he would murmur prayerfully, ‘If I could only see.’ In going down to defeat, Armstrong exhibited a brand of courage that will cause him to be long remembered even if he had not in the past held the featherweight, lightweight, and welterweight championships of the world simultaneously.”

The last of Armstrong’s three championships was gone.

On January 17, 1941, Armstrong and Zivic fought again. A standing-room-only crowd of 23,190 (the largest in the history of Madison Square Garden) witnessed the battle. Five thousand more fans were turned away.

Zivic dominated from beginning to end, beating Armstrong as brutally as Armstrong had beaten Barney Ross.

James P. Dawson wrote, “Armstrong was pelted from all angles and with every blow known to boxing. Zivic handled him as he willed, spearing and cutting him at long range, battering the daylights out of him at close quarters. By the sixth round, Armstrong was uncertain of his footing as he shuffled forward. His eyes, swollen from the fourth on, were ripped open in the eighth. In the ninth and tenth, Armstrong was pounded almost beyond recognition.”

After round ten, referee Arthur Donovan told the badly battered Armstrong that he would give him one more round.

“Armstrong,” Dawson recounted, “responded to this warning with a flash of the fighting demon of old. Through the eleventh round, he pulled the crowd to its feet in as glorious a rally as this observer has seen in twenty-five years of attendance at these ring battles. The former champion hammered Zivic all over the ring. He pelted the titleholder with lefts and rights to the body, plied him with savage thrusts of the left and wicked right smashes to the head and face, blows with which he hoped to turn the tide of crushing defeat that was engulfing him. For two minutes, Armstrong went berserk. He was a fighting maniac, the Hammering Henry of old. It was glorious spectacle while it lasted. Then Zivic stepped to the attack. Through the last minute of the eleventh round, he hammered Armstrong mercilessly with short chopping stinging lefts and rights that ripped open old wounds and started a flow of blood.”

Donovan stopped the fight in the twelfth round. Afterward, Dr. Alexander Schiff of the New York State Athletic Commission warned Armstrong that he risked going blind if he fought again.

After the second Zivic fight, Armstrong said that he was done with boxing. His championship days were gone and he had no desire to fight again. Then a predictable problem surfaced: money.

Armstrong had made over a million dollars in purses. But management had taken a generous share. He’d lost money on several business ventures, including a Chinese restaurant in Hollywood and the Henry Armstrong Melody Room in Harlem. He’d partied with a lot of women and thought of himself as “a rich playboy, flashing around town in a yellow convertible.” He was a soft touch for handouts.

“Too many night clubs,” he acknowledged in his autobiography. “Too many $1,000-dollar bills. Too many fine cars, fine clothes, fine parties. The money was rolling in. But the money was also rolling out.”

On June 1, 1942 (sixteen months after being knocked out by Zivic), Armstrong returned to the ring in San Jose, California, against a club fighter named Johnny Taylor.

“I was there that night,” promoter Don Chargin remembers. “I was a kid. I didn’t know much then. But I was amazed. Armstrong was on a downward slide, but he still had an aura about him and he was still perpetual motion. All the way from his dressing room, up the aisle into the ring, he was throwing punches. While he was waiting to be introduced, he was throwing punches. Then the bell rang and he kept throwing punches. He knocked Taylor out in the fourth round. Three months later, they fought again and Armstrong knocked him out in three rounds. Years later, I asked Taylor, ‘You took such a beating the first time; why did you fight him again?’ And Taylor told me, ‘It was an honor being beaten by him.’”

Armstrong fought fourteen times in 1942, winning all but once. Ten victories in twelve fights during the first eight months of 1943 followed. “Every fighter tries a comeback,” he said. “It’s hard to quit the only job you know. There’s always some money to be made, even on the other side of the hill.”

But as Barney Ross noted from his own personal experience, “When you start to slide in this racket, nobody can stop it. There’s only one way to go. Down.”

On August 27, 1943, Armstrong fought Sugar Ray Robinson at Madison Square Garden. Robinson had a 44-and-1 record with 30 knockouts and was twenty-two years old. His boyhood idol had been Henry Armstrong. After a storied amateur career, Sugar Ray had made his professional debut with a second-round knockout of Joe Echevarria at Madison Square Garden on October 4, 1940; the same night that Armstrong lost his welterweight championship to Fritzie Zivic.

Robinson carried Armstrong for ten rounds. And everyone in the arena knew it.

Joseph Nichols wrote of the fight, “Ray Robinson enjoyed a brisk workout at the expense of veteran Henry Armstrong in the star bout of ten rounds at Madison Square Garden last night. Robinson enjoyed it, but nobody else in the Garden got any satisfaction from the spectacle which was as tame as a gymnasium workout between father and son. Going along quite as he pleased, Robinson handled the one-time triple champion exactly as he was, a has-been whose best days were far behind him. Robinson, with the speed and agility that go with his 22 years, merely pecked away at his opponent, riddling him with a ceaseless spray of long lefts to the head. On infrequent occasions, the New Yorker essayed a right-hand punch to the head. Some of these blows landed, albeit with little force. Most of them missed, and by such wide margins that several critics were moved to observe that Ray was of no mind to punish the ex-champion. Each of the ten rounds was a repetition of the other nine.”

“I’d hit him enough to get him in a little trouble,” Robinson said years later. “But whenever I felt him sagging, I’d clinch and hold him up. I didn’t want him to be embarrassed by a knockdown.”

“I know it looked bad,” Armstrong admitted to reporters after the fight.

But he kept fighting. Nineteen fights in 1944.

When his career was done, Armstrong would observe, “When you’re champ, you have to keep going to stay on top. You have only a few years to make your money. After that, you’re just another has-been. When you’re through, you’re through. When you’re old, you don’t get young again.”

On January 14, 1945, Armstrong fought to a draw against Chester Slider in Oakland, California. They fought again on Valentines Day, and Slider won a ten-round decision. That was it. The ring career of boxing’s perpetual motion machine had come to an end.

After Armstrong’s boxing days were over, life came at him with the same merciless pounding that he’d dealt out to others in the ring. His management team had kept him fighting regularly so their end of the purses would keep coming in. That had also limited his drinking, which was a problem at times; although there’s a school of thought that fighting as often as he did was one of the factors that drove him drink.

With no fights to train for, there were fewer and fewer days when Armstrong was sober. On a January morning in 1949, he woke up in the drunk tank at a police station in Los Angeles. He’d jumped the curb while driving drunk the night before and crashed his car into a lamppost.

Later that morning, the judge at his arraignment gave him a tongue-lashing, admonishing him that he was “letting a million boys down.”

The following night, Armstrong went out and got drunk again. Then, driving home, he heard what he called the voice of God speaking to him. In that moment, he surrendered to Christ, put his life in God’s hands, and vowed to never drink again. Eventually, he became an ordained minister in the Morning Star Baptist Church, where he was known as “God’s ball of fire.”

“I became friendly with Henry late in his life,” Don Chargin recalls. “He’d given up drinking by then. He was very likable, very talkative, constantly quoting from the Bible. He talked a lot about how his drinking days and carousing days were behind him; that he hadn’t been a very good husband or father when he was young, but that he was a much better person and much happier now that he’d found the Lord. I think he was sincere. He seemed to have peace of mind.”

“I met him in the 1980s,” Don Turner reminisces. “They brought him to Cincinnati to work with Aaron Pryor for a couple of days. Pryor fought like Armstrong used to fight, and his management team thought that maybe Pryor could learn something from him, plus it would be good publicity. It was the sort of thing where you go over to someone you admire and introduce yourself. We talked in the gym for about fifteen minutes, small talk. And it was wonderful. He was a very nice humble man.”

Jerry Izenberg met Armstrong when the fighter testified before a New York State legislative committee that was considering legislation to ban boxing.

“He was talking about the good that boxing can do in a man’s life,” Izenberg recounts. “And the lawyer for the committee was giving him a hard time. Armstrong was blind in one eye, and the lawyer asked him in a very condescending way, ‘How did that happen, Mr. Armstrong?’ Armstrong told him, ‘I was a boxer. It happened as a result of boxing. I was a good boxer. I’m not ashamed of that.’”

But life was hard. In Armstrong’s later years, he lived in poverty and suffered from cataracts, persistent pneumonia, malnutrition, and dementia. He died on October 23, 1988. The cause of death was listed as heart failure.

It’s difficult to take a fighter out of one era and know with certainty how he would have performed in another. But the prevailing view is that Armstrong would have been a champion in any era.

He’s remembered today primarily because he held the featherweight, lightweight, and welterweight titles simultaneously. Putting that accomplishment in a larger perspective, the most credible accounting of his fights lists him as having 149 wins (including 101 knockouts) against 21 losses and 10 draws. In the forty-six months prior to his losing the welterweight title to Fritzie Zivic, Armstrong’s record was 59-1-1. During his reign as champion, he won twenty-one title fights. He was knocked out only twice in his career - in his first pro fight by Al Iovino and in the 131st by Zivic. There was a time when he could beat any fighter in the world from 126 to 147 pounds. And that was during the “golden age” of boxing, when there were a lot of very good fighters.

“Sugar Ray Robinson told me that Henry Armstrong was an alltime great,” Don Elbaum recalls. “Rocky Marciano told me that Henry Armstrong was an alltime great. Willie Pep told me that Henry Armstrong was an alltime great. That tells me all I need to know.”

“I never saw a better small man than Henry Armstrong, and I don’t expect to,” Jack Dempsey said late in life. “They don’t make them like that anymore.”

Thomas Hauser's email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book – The Most Honest Sport: Two More Years Inside Boxing - is available at https://www.amazon.com/Most-Honest-Sport-Inside-Boxing/dp/1955836329/ref=sr_1_1?crid=MLXL6UHY8O9E&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.NZgHyDuy4gb1i6YPJ_9vmAMw3oLJh1d9Sxs-G8xJoJY.67ftevZ4BImTjJoSlE9uPWJz-j5i5wJGtSrlNDVZw-g&dib_tag=se&keywords=the+most+honest+sport+hauser&qid=1750773774&sprefix=the+most+honest+sport+hauser%2Caps%2C65&sr=8-1

In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing's highest honor - induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.