THOMAS HAUSER

Archie Moore Revisited

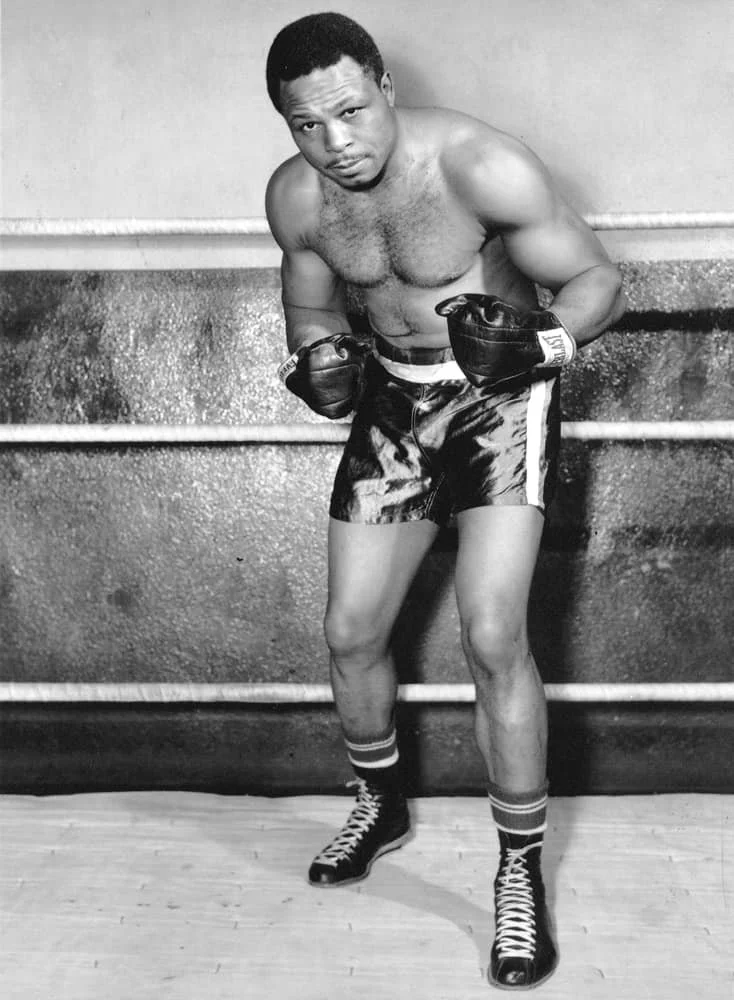

THE SCORECARD / ARCHIE MOORE REVISITED

Archie Moore was a self-educated man who brought a philosophical veneer to a hard brutal sport. He’s revered today, not for a handful of signature fights but as a symbol of skill, craftsmanship, and boxing genius who persevered in the face of adversity and overwhelming odds.

Moore represents the greatest of boxing’s greats and also the thousands of faceless fighters who toiled in his time. Late in life, he reminisced, “In the beginning, I fought for ten dollars a fight. Sometimes I was given a promise, nothing more. Guys like me, we were always marching, fighting, marching, fighting. Most of the time, it wasn’t much fun.”

Moore fought professionally from the 1930s into the 1960s. For years, the Ring Record Book listed his first pro fight as a knockout on an undetermined date in 1935 over an opponent named Piano Man Jones (possibly a misnomer for Piano Mover Jones). Boxrec.com and Moore’s autobiography (The Archie Moore Story) reference his first opponent as one Billy Simms and say that the bout occurred on September 3, 1935.

The Ring Record Book credits Moore with 199 wins (145 KOs), 26 losses (7 KOs by), and 8 draws. Boxrec.com (now a more reliable source) lists 185 wins (132 KOs), 23 losses (7 KOs by), 10 draws, and 1,474 rounds boxed. Those are staggering numbers.

Facts blur when discussing Moore. He was a teller of tales, and even his date of birth is subject to conjecture. His mother said he was born on December 13, 1913. Moore claimed it was three years later. Information in a 1920 census report supports the 1916 date but is not fully dispositive of the matter.

What’s known with certainty is that Moore was born in Benoit, Mississippi; the son of Thomas and Lenora Wright. His mother had previously given birth at age fifteen to a daughter named Rachel. Two years later, Archibald Lee Wright was born.

Archie parents separated when was eighteen months old, and he was sent with his sister to St. Louis to live with his aunt and uncle, Cleveland and Willie Pearl Moore. At that time, he later explained, “I became Archie Lee Moore, for it saved many questions put to my aunt when we moved from house to house. Moore is my name, and it is the name my children have.”

“I idolized my uncle and wanted to be like him,” Moore continued. “And I adore my auntie. Although she never had children of her own, she was a great mother in every sense. She gave us love and affection and taught us all the things a good mother should teach her children.”

Moore went to Dumas and Jefferson grade schools and the Lincoln School, an all-black junior and senior high school in St. Louis. He learned the rudiments of boxing on the streets from friends and enemies alike. Then tragedy struck.

Cleveland Moore died as a consequence of injuries suffered during an initiation rite into a fraternal organization. Soon after, Moore’s sister, who had married a man named Elihu Williams, died while giving birth to twins. One of the twins, a boy, died four months later. Auntie Willie took the other infant (a girl named June) in and raised her as her own.

Meanwhile, Moore’s life was taking a downward turn.

“Moral character is a very pliable thing,” he later noted. “It bends to circumstances. After my uncle’s death, I began to run wild. I turned to petty thievery for personal monetary reasons. Stealing was such an everyday way of life that it was accepted by all of us. We reasoned that it was a matter of survival, a way of life in tough Depression times. I knew that eventually I would be caught. But the desire to have a little spending money forced me to overlook this.”

Moore began by stealing lead pipes and copper wiring out of empty houses and selling the material for scrap. Then he graduated to bolder crimes. He was arrested three times. On the third occasion, a friend named Arthur Knox disconnected the pole from which a streetcar drew electrical power from an overhead powerline. The streetcar came to a halt; the motorman got out to put the pole back in place; and Moore ran onto the car to steal the change from the cashbox. Given his previous arrest record, he was sentenced to three years at the Missouri Training School in Booneville. He was fifteen years old.

The reform school was largely self-sustaining. It had a stone quarry, brickyard, orchard, dairy, butcher shop, bake shop, and laundry. In Booneville, Moore later said, he reached a “personal crossroads.”

“I had burned the bridge of formal education behind me,” he wrote in his autobiography. “I now had a choice of which way to go and what to do. Either I could continue stealing, in which case I knew that I would eventually be caught and sent back to reform school, or prison when I was older; or I could try to get out of the ghetto by pursuit of an honest living.”

Moore boxed while in reform school. By his own count, he registered sixteen knockouts in his first year, which gave him a reputation that the other boys respected.

“During my thinking hours, and I had plenty of them,” he later reminisced, “I decided to make fighting my career. I determined to learn as much as I could, strengthen myself, and turn pro as soon as I was of age. I was paroled after twenty-two months and made a vow that I would never again do anything that would cause me to be sent back to reform school or jail.”

Moore left the Missouri Training School at age seventeen. But as he later recalled, “My boxing aspirations, unfortunately, were all my own. No one shared them. I was seventeen, muscled, and totally without experience in the eyes of the men who made matches or managed fighters.”

It was a condition of his parole that Moore get a job. His first employment was as a delivery man for an ice and coal dealer. But he quit after the first day when the dealer shortchanged him for his work. Next, he found parttime employment as a household domestic. Then he joined the Civilian Conservation Core.

The CCC was a federal program that was part of Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal.” Workers (mostly young men at risk) were paid thirty dollars a month, twenty-five of which was sent home to their families. They also received Army-barracks-style room and board.

Moore was assigned to Camp 3760 in Poplar Bluff, Missouri, and worked in the forestry division, cutting down and removing trees so roads could be carved out of the wilderness. He also helped organize a camp boxing team and further developed his own skills.

On September 3, 1935, some CCC workers including Moore attended a professional fight card in Poplar Bluff. In one of the preliminary bouts, a local fighter named Billy Simms fought an opponent who Moore later described as looking “like he had just jumped off a freight train.”

“The boy quit in the first round,” Moore recalled. “The crowd booed the fight, and Simms made a plea from the ring saying it wasn’t his fault. My pals hollered back, ‘We got someone to fight you,’”

Moore borrowed a pair of gloves, sneakers, and trunks from the promoter, stepped into the ring, and knocked Simms out. No weights are listed for the bout. What’s known is that Moore was five-feet-eleven inches tall and fought his next two bouts the following year at 148 and 145 pounds.

Moore was honorably discharged from the CCC in early 1936 and returned to St. Louis where worked briefly for the federal Works Progress Administration. Then he began to pursue his ring career in earnest.

The world was different then. Boxing and baseball were America’s two national sports. A fighter’s trunks were black or white. There were no roundcard girls or ring-walk music. Boxers didn’t need a TV date to fight. In fact, there was no television. There were eight weight divisions with one champion in each division. Unlike today, a loss wasn’t seen as removing a fighter from title contention. Winning a world championship was akin to becoming a made man.

For years, Moore was forced by circumstances to campaign as a vagabond boxer. Between 1935 and 1937, he compiled a 20-1-2 record, fighting in Missouri, Arkansas, Illinois, Iowa, Oklahoma, Indiana, and Ohio. Then he moved to San Diego, where he won nine fights in a row before returning to St. Louis at the end of 1938. He won five fights in a row in his hometown to bring his record to 33-2-2 before losing a ten-round decision to veteran Teddy Yarosz. After that fight, Ray Arcel (Yarosz’s trainer) said of Moore, “He’ll be a great fighter a year from now. All he needs is experience.”

Moore moved from manager to manager and trainer to trainer during that time, as he would for much of his career. He hustled pool to make ends meet and studied boxing history, reading whatever he could find. After losing to Yarosz, he went west again for eight fights. Then, on January 4, 1940 (three days after marrying Mattie Chapman), he journeyed to Australia on what he later called “my solo honeymoon.”

Moore was in Australia for eight months. His marriage failed to survive the separation. Three later marriages also ended in divorce. But he was undefeated in seven fights down under, winning six of them by knockout. There were four more fights in San Diego. Then near-disaster struck.

In February 1941, Moore suffered a perforated ulcer, underwent surgery, and (by his account) was “in a coma for five days, hovering between life and death.” Peritonitis set in, extending his hospital stay to thirty-eight days. He later claimed that, during his time in the hospital, his weight dropped from 163 to 108 pounds. Midway through his recovery, he suffered an acute appendicitis. He was out of the ring for eleven months before returning to action on January 28, 1942, with a third-round knockout of Bobby Britt. It was the only recorded bout of Britt’s career.

Twenty-two more fights on the west coast followed. Then Moore journeyed east, winning a ten-round decision over Nate Bolden at St. Nicholas Arena in New York. Massachusetts, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Oregon, Wisconsin, Colorado, Washington, Washington D.C., Utah, and Florida were added to his itinerary. He also fought in Panama, Argentina, and Uruguay.

One can only begin to imagine what went through Moore’s mind as he moved from town to town and fight to fight, winning most, losing some, for over a decade. Late in life, he looked back on what he called “the sad lonely days when hardly anybody knew who Archie Moore was. I was just another name in small print on a fight card; just another black kid spilling his blood to make a few bucks to stay alive in the hope that there were better days ahead. I would fight for short money in little towns. Then, my body still clammy with sweat because the little arena had no showers and I couldn’t afford a hotel room, I would ride a dusty dirty bus or freight train to the next town, still hurting and bruised from my last fight. I thought of the filthy, rat-and-bug-infested, two-bit flophouses I had stayed in; and the cheap starchy foods eaten in crummy restaurants; and I thought of even leaner days when I didn’t have a cent in my pocket and I was so hungry and cold and tired that even the cheap food and dirty flophouses would have been welcome.”

The heart of Moore’s problem, legendary trainer Eddie Futch noted, was that “Archie was too good for his own good. He was victimized by his talent. No manager wanted to risk the title against him.”

Veteran promoter and matchmaker Don Chargin puts Moore’s dilemma in further perspective. “If you were a black fighter in those days,” Chargin recalls, “the people in charge would tell you that you had to lie down or you didn’t work. One reason that Archie fought so many tough black fighters early in his career was that neither guy would have to lie down for the other.”

Thus it was that Moore fought twenty fights against Charlie Burley, Eddie Booker, Jack Chase, Lloyd Marshall, Jimmy Bivins, and Ezzard Charles - men he branded along with himself as “the killing row of Negro middleweights.” His composite record against them was ten wins, seven losses, and three draws.

In 1945, ten years after Moore’s pro debut, he moved up to the light-heavyweight division. “I was eaten with ambition and bitter because I never seemed to get my due as a fighter,” he said. But he kept winning, following a simple battle plan

“When I went into the ring,” Moore later recalled, “I kept my thinking calm. I would plan a fight according to my opponent, his abilities and his style. Every move I made was carefully calculated and planned. Even during the heat of battle, I usually managed to keep my thinking organized and follow my plan.”

That plan had a simple foundation.

“A good jab is an absolute must if you want to be a good fighter,” Moore explained. “If you can’t master a good jab, you might as well give it up. A hard body shot will do more damage than one to the jaw. Try to hit your opponent high on the rib cage. When you do, you will hamper his movements on whichever side you hit him, and then you can work on that side more freely. I know it looks sensational to keep hitting a guy in the face. But believe me; it’s body punching that wins fights.”

And there was another essential ingredient.

“I’ve seen many excellent fighters, but the only ones I would bank on would be finishers,” Moore declared. “Without that ability, you just aren’t cut out to be a fighter. In Dempsey’s day, they used to call it the killer instinct.”

How good was Moore?

“He was great,” Emanuel Steward said shortly before his own untimely death. “Some fighters intimidate opponents with a big punch. Moore intimidated fighters with his skills. He was a thinking fighter, very intelligent and analytical. He was patient. He took his time. There was very little wasted energy or movement. As a fight went on, he’d analyze his opponent, find his weaknesses, and figure out what he had to do to break him down. He was very strong physically, crafty, not particularly fast. He’d slip, parry, throw a stiff upjab, get in close. He was always in range where he could make a move and punch. Then, at just the right moment, he’d let that sneaky hard righthand go and knock his opponent out. He knew how to fight. And he had a lot of heart.”

“Moore didn’t have the sheer natural ability of guys like Sugar Ray Robinson or Ezzard Charles,” trainer Don Turner adds. “And he didn’t have the greatest chin in the world. But his defense was so good that he didn’t get hit on the chin that much. He was crafty; he was cunning; he was elusive. He could punch and hurt you in a lot of different ways. The physical conditioning for elite fighters today is better than it was when Moore fought. But the technique that fighters had in those days was much better than it is now. Moore knew what he was doing in the ring. He could set you up, tie you up, do whatever he wanted to do. He had more ways to survive than anyone in the business. He could outthink anyone. He had endless determination. And he used everything he had.”

Moore added victories over light-heavyweight contenders Holman Williams, Bob Satterfield, and Harold Johnson to his resume. But his championship quest remained unfulfilled.

“I fought many years longer than I should have had to before I got a shot at the title,” he later wrote. “I felt like a guy trying to climb a glass mountain. I would climb two steps up and then slide four steps back. I scratched and clawed my way up that glass mountain until I could almost touch the peak with my outstretched fingertips. It was like a bad dream where you’re trying to reach something but never can.”

On July 24, 1950, Joey Maxim won the world light-heavyweight championship with a tenth-round stoppage of Freddie Mills.

“We ducked Moore just like everybody else was doing,” Doc Kearns (Maxim’s manager) later acknowledged in his autobiography. “He was too smart, too skillful, too experienced, and carried too many blockbusters in his arsenal to take him on before we were forced into it.”

Instead, Maxim fought a series of non-title fights, challenged Ezzard Charles unsuccessfully for the heavyweight crown, and prevailed over Sugar Ray Robinson, when Robinson wilted in the 104-degree heat at Yankee Stadium and was unable to come out for the fourteenth round.

Meanwhile, Moore had come to understand that, to force a championship fight, he had to create a public persona and get public opinion on his side.

“When Maxim won the title,” Moore later recalled, “I really began to campaign in earnest. Eddie Egan was commissioner of boxing in New York State. I ran into him in the lobby of Madison Square Garden. He had been a great amateur light-heavyweight, and I thought he would be in sympathy with my plea. I approached him and told him who I was and what I wanted. He almost snapped my head off with a surly reply, saying he was a commissioner and not a matchmaker. He swept me aside like a bread crumb on a waiter’s tip.”

Undeterred, Moore mounted an extensive letter-writing campaign to sportswriters around the country, penning as many as thirty letters a day. Typicial of these missives was one sent to Dan Parker of the New York Mirror:

Dear Mr. Parker,

Knowing of your unbiased reputation as a top sports writer, I felt I could appeal to you. As the number one contender for the light-heavyweight title held by Joey Maxim, I am avoided by him. He steadfastly refuses to fight me, choosing instead men who are in the second division. In addition to being unfair, this casts a negative light on boxing. Please use your column to tell your readers of the state of affairs in professional boxing.

Sincerely,

Archie Moore.

It was also around this time that Moore began referring to himself as The Mongoose, explaining, “The mongoose is a cagey and fierce animal; so fierce that he will fight the dreaded cobra, depending on technique to combat the cobra’s swift and deadly blows. The mongoose is faster and he can feint the cobra out of position by waiting until the very last moment to move, making the cobra miss and miss and miss until he fails to retract effectively. The mongoose then moves in for the kill, seizes the cobra under the throat, and crushes his skull.”

In 1951, Robert Christenberry succeeded Egan as chairman of the New York State Athletic Commission. Christenberry was more receptive than Egan had been to Moore’s pleas. The National Boxing Association also supported Moore’s cause.

More significantly. Moore agreed to retain Doc Kearns as an advisor and pay him a portion of his future earnings in exchange for a title opportunity.

“Doc Kearns is a sentimentalist about money,” Archie noted.

And Moore agreed to a bout contract that guaranteed Maxim a $100,000 purse. Given the economics of the situation, that meant Moore would receive virtually nothing. Ultimately, his purse for the fight was eight hundred dollars.

On December 17, 1952, at age thirty-six (or thirty-nine) in his 160th professional fight, Moore finally got the opportunity to fight for a world title.

“It’s hard to describe my feelings when I fought Maxim for the championship,” he wrote in his autobiography. “In a way, it was almost anti-climactic because, when I received the word that I was to fight him, that was really the climax. I was sure I would win, and yet I wasn’t sure. It’s like a student who is about to take an important examination. He is confident that he will pass, but he isn’t sure because he’s not certain what questions will be thrown at him. That was the way I felt about Maxim. I knew I could beat him if I didn’t get careless. Any fighter can be knocked out if hit hard enough in the right place, and there was always that possibility against a first-class opponent like Maxim. So while I was sure I would win, I wasn’t sure. Anything could happen in a fight.”

Maxim-Moore took place in St. Louis. Moore dominated throughout the bout and won a lopsided unanimous decision.

In his dressing room after the fight, Maxim told reporters, “These guys don’t grow old. They just get better as they go. Moore is a better fighter than Ray Robinson. That sneaky right hand that he throws is murder. I knew he was good. I thought he would weaken in the late rounds, but he got stronger as the fight went on. Boy, is he tough.”

As for the new champion --

“I was happy and proud after beating Maxim,” Moore later recalled. “The morning after the fight, I bought the newspapers and sat there grinning like an idiot as I read that Archie Moore was the light-heavyweight champion of the world.”

Part Two

“Becoming champion created a new world for me,” Archie Moore wrote in his autobiography. “It was tangible proof that I was doing a good job in my chosen profession. It fulfilled a need everybody has - the need to feel important. Winning the championship was also the fulfillment of a dream. And it’s nice to have dreams come true.”

As champion, Moore married for the fifth time. His new bride was a model named Joan Hardy, whose sister was married to actor Sidney Potier. The Moore-Hardy union lasted until his death. Together, they had two daughters and three sons.

Meanwhile, Moore’s ring career went on. In the fifteen weeks after beating Maxim, he won six over-the-weight non-title fights, including a unanimous decision over heavyweight contender Nino Valdes. On June 24, 1954, he decisioned Maxim in a contractually-mandated rematch. That was followed by two over-the-weight non-title bouts in Argentina and a third fight against Maxim.

“For years,” Moore later observed, “I couldn’t get near Maxim. And now I couldn’t get away from him.”

That was because Doc Kearns still managed Maxim in addition to having a piece of Moore.

“If it weren't for fight managers,” Moore grumbled, “a lot more fighters would have been millionaires.”

During this time frame, Moore also began to have trouble making the 175-pound weight limit. That led to some unusual practices.

Moore claimed that he had learned invaluable nutritional secrets from an Aborigine while fighting in Australia in 1940. Being a teller of tales, Archie confided, “I was given a secret recipe by a dying Aborigine under a gumtree in a desert near Wootawoorwoorowwoora. At least, I figured he was dying. He looked mighty sick. And he made me promise I would never tell the secret of this semi-vanishing oil until he died. Well, how do I know he’s dead? I ain’t taking no chances.”

Speaking of the Aborigines on another occasion, Moore maintained, “They were all quite lean and possessed tremendous stamina. They attributed this to the fact that they would chew on strips of meat, chewing until the last bit of juice had been extracted. This would nourish them and keep up their strength without adding any weight. They never swallowed the bulk of the meat from which they had extracted the juice. Of course, this chewing meat without swallowing it is not an easy thing to do. It takes great control to keep from swallowing a delicious piece of meat instead of just chewing on it and swallowing the juices before spitting out the bulk.”

Publicist Bill Caplan, who spent time with Moore, says simply, “It wasn’t pleasant eating with Archie when he was trying to make weight. He’d chew the meat for the juice and spit the rest out on his plate. No napkin or anything like that. Just chew, spit, chew, spit.”

Following his third triumph over Maxim, Moore won three more over-the-weight non-title bouts and successfully defended his championship against Harold Johnson and Bobo Olson. Then he reached for the stars.

For much of the twentieth century, the heavyweight championship was the most coveted prize in sports. Three months prior to Moore beating Maxim to claim the light-heavyweight title, Rocky Marciano had knocked out Jersey Joe Walcott to annex the heavyweight throne.

Reprising a tactic that he’d used to get his title opportunity against Maxim, Moore sent hundreds of handwritten letters to sportwriters around the country urging them to support a Marciano-Moore fight. That was followed by press releases, classified ads, and a “wanted” poster offering a reward for the capture and delivery of Marciano to “sheriff” Archie Moore.

“I got Marciano in a corner,” Moore later reminisced. “People would ask him when he was going to fight me, and he could no longer say, ‘I don’t want to hurt that old man.’ He had to either fight me or face the embarrassment of refusal the rest of his fighting career.”

Marciano-Moore was contracted for and scheduled for Yankee Stadium. The challenger carried the brunt of the pre-fight promotion. Jerry Izenberg (then a cub reporter) recalls, “Archie was a blessing to the writers. He always gave us something we could write.”

In the weeks leading up to the bout, Moore was often seen wearing a blue yachting cap. “It lends an impression that you own a yacht,” he explained.

He also got maximum publicity out of his dietary habits by putting a lock on the training camp refrigerator and claiming that his nutritional secrets were “too valuable to be left lying around.” A screen was erected around his table during meals to protect against prying eyes. In a similar vein, Moore carried a flask that he sipped from occasionally and told reporters that it was a secret brew prepared from a recipe given to him by a tribe of Aborigines in Australia

“If the outcome of the fight was dependent on conversation,” Arthur Daly of the New York Times noted, “Marciano wouldn’t have a chance.”

On September 21, 1955, a crowd of 61,574 filled Yankee Stadium for Marciano-Moore. Former heavyweight champions Jack Dempsey, Gene Tunney, Max Baer, James Braddock, and Joe Louis were at ringside. Another 400,000 fans watched the fight on closed-circuit television in 133 theaters across the country.

Moore’s purse was $270,000; the largest of his career (equivalent to $3,280,000 in today’s dollars). Marciano received $471,000. Moore weighed in at 188 pounds; Marciano, a quarter-pound heavier. The most youthful estimate dated Moore as three months shy of thirty-nine years old. Whatever his age, he was well past his prime. Marciano, an 18-to-5 favorite, was thirty-two.

Moore was a showman. After beating Maxim, he’d ordered custom-made robes for many of his fights. In his title defense against Harold Johnson, he’d entered the ring wearing a black satin robe with a gold satin lining, mandarin collar, and ten-karat gold edging. For Bobo Olson, he unveiled a white English flannel model with a gold satin lining, gold braids, and ten-karat gold epaulets.

Against Marciano, Budd Schulberg reported, “Moore entered the ring in a flowing regal robe of black brocade trimmed in gold with Louis XIV cuffs and a brilliant gold lining, under which he affected another silken robe of saintly white. Aeneas himself could not have born himself more proudly. Whether the venerable pugilist is truly a god or merely a fine play actor who has a way with Homeric material, I know that the gods of ancient Greece and Rome would have been delighted with him.”

The fight itself was high drama.

“At the opening bell,” Moore later recounted, “I came out of my corner to meet Marciano, and strangely enough he started backing away. I jabbed several times, but they went over Marciano’s head as he was boxing pretty low. I thought I would change tactics and make him straighten up because he was pretty hard to hit while in the crouch. So in the second round, I feinted Marciano and took a half-step back. As he followed me in with a short overhand right, I took another short step backward so that he missed me by three inches and I came through with an uppercut that hit him right on the chin and he went down heavily on one knee and both elbows.”

For only the second time in his career, Marciano was on the canvas. “I was dazed,” he admitted afterward. “But my head cleared quickly.”

Marciano rose at the count of two. Two minutes and thirty seconds were left in the round. Moore later contended that referee Harry Kessler erroneously began a mandatory eight-count, forgetting that the eight-count rule was not in effect for title fights.

“Rocky was a wide-open target at that point,” Moore claimed. “Dazed, confused, and with absolutely no defense and no mobility. It would have been like hitting a punching bag. If I could have gotten him when he got up after the two count, I could have become heavyweight champion.”

But film footage of the fight is at odds with Moore’s version of events. It shows that the action resumed within three seconds of the time that Marciano rose from the canvas. Kessler didn’t even wipe off his gloves.

Marciano survived the second round. Then, inexorably, he wore Moore down with brute force, battering his arms, upper body, and every other part of his anatomy that could be hit with heavy sledgehammer blows.

"Rocky didn't know enough boxing to know what a feint was,” Moore mused years later. “He never tried to outguess you. He just kept trying to knock your brains out. If he missed you with one punch, he just threw another. Of all the guys I fought, Marciano hit me harder than everybody else combined. I felt like someone was beating all over my body with a blackjack or hitting me with rocks.”

“I don’t think I ever threw more punches in a fight than I did tonight,” Marciano told reporters when it was over. “I just couldn’t seem to get a clean shot at him. He’d hide beneath those arms and bob and weave and roll with the punches, so the only thing I could do was keep pitching them.”

Marciano put Moore on the canvas twice in the sixth round. In round eight, Moore was knocked down for the third time but was saved by the bell. In round nine, he was counted out. “I had the braggadocio and the skill and the guts,” he acknowledged. “But that wasn't enough. Marciano beat me down."

Of the final rounds, Budd Schulberg wrote, “The golden-robed god of the fistic wars was getting the hell beat out of him. The cestus-like fists of Marciano were punishing the old man terribly. The Greeks would have wept for Moore. In the end, he sat there in great sadness as the referee administered the fight game’s numeric version of the last rites. There was tragedy in the way he sprawled there with the fight and the will beaten out of him; a very old man of forty-two who, some thirty minutes earlier, had been such an astonishing young man of forty-two.”

Years later, Moore would look back on his conqueror and that night with a mixture of sadness and pride.

“The Marciano fight was like a dream come true,” he wrote. “This was the one fight that I had always wanted – a fight for the heavyweight championship of the world. It is a bout I will always cherish. The cheer that went up when I decked Marciano was the most thrilling and inspiring sound I have ever heard. You cannot imagine what the roar of sixty thousand people can do to your spine. You stand under the lights with a fallen champion at your feet and, as one voice, the crowd salutes you. It is a thrill that cannot be measured. It is a memory I can conjure up by just closing my eyes. When I was knocked out, the same crowd saluted Rocky, and that is as it should be.”

After losing to Marciano, Moore, in essence, told the boxing establishment, “You wouldn’t let me fight for the light-heavyweight championship when I was in my prime. Why should I give it back to you now that I’m old?”

Over the next year, he engaged in a well-orchestrated sleight of hand that saw ten over-the-weight non-title fights against mediocre opponents and one championship defense in London against the non-threatening Yolande Pompey. Then opportunity knocked once more.

Seven months after beating Moore, Rocky Marciano retired from boxing without fighting again. The powers that be then decreed that Moore should be matched against Floyd Patterson for the vacant heavyweight throne.

Moore-Patterson was contested in Chicago on November 30, 1956. Had Moore won, he would have been the oldest man as of that time to claim the heavyweight crown. As it was, Patterson, age twenty-one, became the youngest. He knocked Moore out in the fifth round.

Moore was simply too slow.

“I trained hard for the Patterson fight,” he said afterward. “Too hard; I overtrained. I was stale. Patterson didn’t surprise me when we fought. I knew what type of fight to expect and I got it. I planned to bring the fight to him and I wasn’t able to. My reflexes were off and my timing was terrible. I was beaten as badly as I have ever been beaten in my whole ring career.”

Moore had two more over-the-weight non-title fights after his loss to Patterson. Finally, on September 20, 1957, he entered the ring to defend his championship against a credible challenger for the first time in more than three years.

Twenty-two-year-old Tony Anthony was the opponent. Four months earlier, Moore had weighed 206 pounds for a fight against Hans Kalbfell in Germany. On the day of the Anthony fight, the Old Mongoose (as he was now known) had to get on the scales six times before making the 175-pound weight limit. Then he knocked Anthony out in the seventh round.

“He’s the Einstein of boxing,” the vanquished challenger said afterward.

“It's my candy,” Moore said of his title. “And the only way you're going to get any of it is to take it away from me.”

Twelve more over-the-weight non-title fights followed. Moore journeyed to Canada, Germany, and Brazil, and added Nevada and Kentucky to his itinerary.

“Do you know why I can continue on while others fade away?” he asked before answering his own question. “I am a man who has more faith in himself than others. Every day, I do something to improve my skill of the game, whether it is refining an old move or mastering a new one. I never stop learning. I realize age is just a number.”

But the most fabled episode in Moore’s ring career lay ahead. By late-1958, according to the Ring Record Book (which was considered the final authority on boxing records at that time), he had accumulated 126 career knockouts. That placed him in a tie with Young Stribling, a light-heavyweight from Georgia, who was credited with 126 career knockouts before his death in a 1933 motorcycle accident.

Then Moore signed to defend his championship in Montreal on December 10, 1958, against a French-Canadian fisherman named Yvon Durelle.

“I’m aware that many observers tend to regard Durelle as just a rough club fighter with no style or class,” Moore said of the impending contest. “I fought another fellow who fit this description – Rocky Marciano. Durelle is like one of those pit bulldogs that are bred to fight to the death. He never steps back. A fighter like Yvon is out only when the referee counts him out. You can’t knock him out with a typewriter or a verbal opinion. December 10th could be the roughest night of my seven-year reign as 175-pound king.”

In truth, Moore thought that Durelle was an easy mark. Archie appeared at the weigh-in attired in a tuxedo, camel’s hair coat, and Homburg hat accessorized by a silver-headed cane. Durelle wore work pants, an old sweater, and rubber boots. Always the showman, Moore approached his opponent and asked, “Who is your tailor?” He then told reporters, “I am counting on Monsieur Durelle showing proper respect for a man old enough to be his father.”

Durelle entered the ring on fight night knowing that he had a tough task ahead of him. Moore had no such foreknowledge. The eleven rounds that followed are now part of boxing lore.

Fifty-five seconds into round one, Durelle landed a perfectly leveraged short righthand flush on Moore’s jaw. Moore dropped to the canvas like he’d been shot. Through an act of Herculean will, he rose to his feet a fraction of a second before the count of ten.”

Lester Bromberg, who was at ringside for the New York World-Telegram and Sun, recounted the impact of the blow that knocked Moore down for the first time: “The punch landed with the impact of a Marine battalion hitting a beach. Moore’s legs instantly sagged. The shock running through his body appeared to disjoint it and he came down backwards like children’s miniature blocks, his head rapping the floor loudly. If the punch hadn’t stunned him, the smash of the back of his head would have. This clearly was a punch-paralyzed man, his right arm stretched limp, his left balanced strangely on his elbow, his torse flat to the thighs, and his right leg crooked in an inverted V. The French-Canadian fans were on their feet, screaming wildly. The gauche fisherman had nailed the defensive master. At five, Moore was still on his back . . . Six, seven, eight . . . Archie hauled himself to a knee. Nine . . . He managed to beat ten, but his feet could not have been heavier if he were mired in sand.”

Dazed, Moore lurched around the ring, unable to defend himself. Durelle pounded him from post to post and felled him with a glancing left; then decked him for the third time with a brutal right hand. A minute and ten seconds remained in the round. Moore barely made it to his feet at nine. Boxing’s ageless warrior looked ageless no more.

In later years, Moore would recount that first round as follows:

* “The fight was about a minute old when he caught me with a right hand. I didn’t see the right hand, but I felt it. It seemed like a bomb exploded in my head. The first thing that struck the floor was the back of my head. I felt a trickle of blood inside my mouth. I knew I had a concussion. I thought, ‘Well, this is the way they happen.’ I guess if I hit my head that hard on the street, I would have been killed.”

* “The first thing I heard was number five. I knew I had to get to my feet, but it felt as if the top of my head was blown off. I rolled to one knee. I think I was up at nine. Then he hit me again, and I thought he'd broken my head. I said to myself, ‘Well, I guess this is the end for me, but I'm going to fight this son of a bitch. I'll die fighting him if it comes to that.’"

* The noise that Canadian crown made was deafening. It sounded like the drone of a million bees in a small room. Over the roar of the fans, I could hear the referee shouting the count in my ear. And I could hear my cornerman begging me to get up. I pushed myself to my feet. Then I was flat on my back again. Once again, I staggered to my feet. I came in with a left hook, and he split me with a right hand and I went down again. I thought, ‘Oh, my goodness; this guy really can hit. And I began to pray softly to myself, ‘Oh, God; if I can just last this round and get to my corner.’ Somehow, I managed to get to my feet. Finally, the bell rang and I stumbled to my corner.”

In round four, Moore took the initiative. But less than a minute into round five, Durelle backed him into the ropes and landed a hard right high on the cheek that put the champion on the canvas again. Moore rose on wobbly legs. Once again, the end seemed near. Amazingly, he survived the round.

Then, remarkably, the fight turned.

In round seven, Moore knocked Durelle down. Ten seconds before the end of round ten, a barrage of punches put the challenger on the canvas for the second time. He rose on unsteady legs at the count of eight and was saved by the bell. At the start of round eleven, a six-punch barrage punctuated by a left hook to the jaw put Durelle on the canvas for the third time. Now the tables were turned. He struggled valiantly to his feet at the count of nine and Moore ended matters with a straight righthand that matched the blow Durelle had begun the carnage with in round one.

“The title is all I’ve got,” Moore told reporters when the fight was over. “I just couldn’t give it up.

“A champion,” Jack Dempsey once said, “is someone who gets up when he can’t.”

Anyone who wants to learn about the heart of a champion should watch round one of Moore vs. Durelle on YouTube. Years later, Moore would reflect back on that night and observe, “The fight with Durelle was the fight that every fighter hopes to have. This is the fight that a fighter dreams about; getting knocked down and then being able to get up and conquer his opponent. I had always known that I would come to the end of the road someday. No fighter lasts forever. And I was in my forties, so losing after all these years was excusable. But there is no excuse for a champion not putting up the best fight he possibly can.”

Part Three

Moore’s 1958 fight against Yvon Durelle was the star atop the Christmas tree of the Archie Moore legend. The bout was the first title fight held outside the United States to be televised live in America. And it captured the imagination of the nation.

The following weekend, Moore flew to New York and was introduced from the audience on The Ed Sullivan Show. At year’s end, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored him as its “Fighter of the Year.”

Jack Murphy of the San Diego Union-Tribune summed up the accolades, writing, “After nearly a quarter-century of fighting in tank towns and eating in greasy spoons, Archie Moore is finally getting the recognition and popularity he so richly deserves. In the aftermath of his spectacular brawl with Yvon Durelle, a lot of people have suddenly discovered that Moore isn’t just a swaggering old con man engaged in a shell game with the public. There is a new appreciation for his exceptional fighting skills and an admiration bordering on awe for his courage. This was a fight that revealed what some of us have been saying for quite a spell. Moore is a fighter for the ages.”

It has been said that Moore was more than a fighter. But that’s true of all boxers. What separated him from other fighters (and athletes) was that, in addition to his skills, he fervently wanted to be recognized as a thoughtful multifaceted man. And he was.

Moore had a way with words. Recounting how his half-brother, Louis, was arrested, Archie explained, “Louis was light-fingered by nature. Somehow, a man’s watch got tangled up in his hand, and the man sent the police to ask Louis what time it was.”

Very few writers can craft phrases like that.

“I liked him very much,” Jerry Izenberg says. “His demeanor always matched the occasion. He was a terrific fighter and a fascinating guy. And I’ll tell you something else. He was better than Ali at conning someone. With Ali, you laughed and you knew he was conning you. With Archie, you didn’t always know that you’d been had.”

“I met him several times,” Emanuel Steward reminisced. “He was a wonderful man. Talking to him was like talking with a college professor.”

Following his victory over Durelle, Moore’s cachet was such that Samuel Goldwyn cast him as Jim, the runaway slave, in a 1960 film version of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

“I was intrigued at the idea of making myself into another person,” Moore said of his film role. “I wasn’t put in the picture as a freak attraction to sell tickets. I honestly think I turned in a performance and not an appearance.”

Hollywood agreed. In the ensuing years, Moore would have roles in The Carpetbaggers (starring George Peppard, Carroll Baker, and Alan Ladd), The Fortune Cookie (with Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau), and television shows ranging from Perry Mason to Batman.

Meanwhile, Moore’s ring career went on. On August 12, 1959, he fought a rematch against Durelle in Montreal. This time, he was properly prepared and knocked the Canadian out in the third round.

There were more over-the-weight non-title bouts. Moore discovered Texas and fought there three times in addition to doing battle in Italy and the Philippines. On October 25, 1960, the National Boxing Association stripped him of his championship for refusing to defend the title against a credible challenger. That left New York, Massachusetts, and California as the only jurisdictions to recognize the legitimacy of his championship claim. He had one final title defense; a fifteen-round decision over Giulio Rinaldi at Madison Square Garden on June 10, 1961. Then those three states also withdrew recognition of his crown.

Moore’s last six fights were fought as a heavyweight. He scored knockout victories over Pete Rademacher, Alejandro Lavorante, and Howard King. Then, weighing 201 pounds, he battled to a ten-round draw against future light-heavyweight champion Willie Pastrano.

Pastrano later recounted that, at the pre-fight physical, Moore couldn’t read the eye chart: “He was saying ‘A . . . B . . . C . . .D.’ The doctor says, ‘For Chrissakes, Archie; that’s not right.’ Archie says, ‘Well, Willie ain’t gonna be that far away from me.’”

By then, Moore had bought 120 acres of land near San Diego and built a training camp called “The Salt Mine. In addition to preparing for his own fights, he’d begun working with other boxers. One of the young men he trained briefly was an eighteen-year-old heavyweight with a 1-and-0 record - a former Olympian named Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. Their union lasted about a month in late-1960 before Clay rebelled against the discipline and housekeeping chores that Moore imposed on trainees and returned home to Louisville.

Two years later, on November 15, 1962, Clay and Moore met in the ring. Their confrontation was typical of boxing; a young up-and-coming fighter against an over-the-hill “name” opponent. Moore was being paid for his marquee value. Yet elements of the match-up were intriguing. Clay had been in fifteen professional fights. Moore was a veteran of more than two hundred. And more important from a promotional point of view, they were boxing’s greatest outside-the-ring showmen

As expected, Moore-Clay was preceded by verbal pyrotechnics. Cassius predicted that “the old man” would fall in four. Moore responded, “I don’t enjoy being struck by children,” and added, “I view this young man with mixed emotions. Sometimes he sounds humorous, but sometimes he sounds like a man that can write beautifully but doesn’t know how to punctuate. Clay can go with speed in all directions, including straight down if hit properly. I have a good solid right hand that will fit nicely on his chops. The only way I’ll fall in four is by toppling over Clay’s prostrate form.”

Clay was a 3-to-1 favorite. The fight was contested in Los Angeles, where 16,200 fans paid a California indoor record of $182,600 to see the bout.

“My plan when I went into the fight,” Moore later explained, “was to move around and catch him with hooks to the body because no one had hit him to the body much. Slow him down and then maybe get him with a sneaky right hand. But his speed was too much for me, and I was made for him in that I used a wrap-around defense to cover up. I would leave the top of my head exposed, and that’s what he wanted. You see, he had a style; he would hit a man a lot of times around the top of the head. And if you hit the top of a man’s head, you disturb his thoughts. A fighter has to think. But if someone is plunking you on top of the head, you cannot think correctly. And this is what he did. He made me dizzy and he knocked me out.”

Four months after losing to Clay, Moore entered the ring for the last time. On March 15, 1963, he fought 39-year-old professional wrestler named Mike DeBiase, who had issued a challenge to Moore after Archie refereed one of his matches.

Only eight hundred fans attended Moore-DiBiase. The gate was under two thousand dollars. It was DiBiase’s first pro fight and it wasn’t pretty. Moore ended matters at twenty seconds of the third round.

After retiring as an active fighter. Moore faced new challenges. “Twenty-nine years of a man’s life aren’t dumped that easily,” he wrote. “I had so many memories that, when I thought of having left the ring forever, it gave me a kind of empty feeling.”

But he soon found other horizons, becoming actively involved with a number of youth programs. It was more than a hobby or public relations gesture. He took the work seriously and invested an enormous amount of time and energy in helping to mold young men and women. There were various business ventures. And he continued training other fighters; most notably, George Foreman.

Moore was with the Foreman team when George upset Joe Frazier in Jamaica in 1973 to claim the heavyweight crown, and also one year later when he lost to Muhammad Ali in Zaire. When Foreman began his comeback in 1987 after ten years away from boxing, he again sought Moore’s counsel. Given the need to slim down from three hundred pounds, Big George considered the merits of Moore’s “Aborigine diet.”

“I would try some of the things, chew the meat and not swallow it, things of that nature,” Foreman said afterward. “But when Archie wasn’t looking, I’d eat it.”

Moore had aged well as a fighter and that continued to be the case long after his ring career was over. He remained mentally sharp in his old age; no mean achievement for a man who’d had more than two hundred professional fights.

Late in life, reflecting on his ring accomplishments, Moore saw himself in the arc of history. “A Negro champion feels he stands for more than just a title,” he observed. “He is a symbol of achievement and dignity.”

And he expressed pride in what he’d accomplished as a boxer.

“It makes me proud when someone mentions that they would sit by the radio and listen to my fights or when someone is excited just to shake my hand,” Moore declared. “I’m proud that I beat fighters who were young enough to be my sons. I am very proud of being able to say that I dropped Rocky Marciano when I fought him. Life’s road is not always smooth. But if you haven’t had any bad times, how can you appreciate the good ones? My rugged road was very interesting and rewarding at the end.”

He often travelled with a 16-millimeter film of his first fight against Yvon Durelle and showed it to anyone who was interested if a film projector was available.

In 1994, Moore underwent triple heart-bypass surgery. He died in San Diego on December 9, 1998.

Archie Moore knew the craft of boxing as well as anyone. He had remarkable skills. But what sets him apart from other fighters is his longevity.

Fighters got old younger in those days. Joe Louis won his last championship fight at age thirty-four. Rocky Marciano fought for the last time twenty days after his thirty-second birthday. There were no modern conditioning techniques, no miracle surgery, and no performance enhancing drugs to prolong an athlete’s career.

Three fights stand out in Moore’s legacy: his winning the title from Joey Maxim at age thirty-six (or thirty-nine); his unsuccessful challenge against Rocky Marciano three years later; and his first fight against Yvon Durelle, when, by any count, Moore was well into his forties. The victory over Maxim was vindication for past wrongs. His efforts against Marciano and Durelle were flawed but heroic performances.

“I always went into the ring feeling that I could beat my opponent,” Moore said of his ring career. “It didn’t always happen that way, but I have a gift for understatement when talking of my losses. I recall the determined feeling I had to do better the next time when I lost, and the wonderful feeling I had when I won.”

Offering thoughts with regard to his place in boxing history, Moore declared, “I must admit that I feel Archie Moore ranked up there with the best. Joe Louis was the best heavyweight I’ve ever seen. John Henry Lewis was the best light-heavyweight. But if anyone wants to dispute this and throw my name in, I’ll listen to the discussion with rapt attention.”

Hall of Fame matchmaker Bruce Trampler, a student of boxing history, observes, “You look at films of fighters and you make allowances for different conditioning and how technique has evolved and you project in your mind what someone like Jack Johnson would be a hundred years later. But at the end of the day, either a fighter has it or he doesn’t have it. Archie Moore had it. He could fight.”

Emanuel Steward proclaimed, “Archie Moore was incredible, one of the alltime greats. They don’t even teach what he could do anymore. To be as good as he was for as long as he was; he might have been the greatest light-heavyweight of all time.”

As for Moore the person; Archie could be irascible, stubborn, prickly. But he was also capable of great kindness. After Floyd Patterson was knocked out by Ingemar Johansson in 1959, Moore sent the following letter to the man who had crushed his own heavyweight championship dreams three years before:

Dear Floyd,

The first bout is over. I know how you must feel. I hope you don’t continue to feel bad. The same thing has happened to many great fighters. I hated to lose to you, and fate decreed it that way. Fate does strange-seeming things. If you are a believer [that] things happen for the best, listen to this and you can find your way out of a seeming tunnel.

Johansson was not so great. You fought a stupid battle. Look at the film. Evaluate it. Never once did you lead with a jab. All you did was move your feet and try to leap toward him. Now this man could bang a little. You gave absolutely no respect to your opposition. If you concentrate on your jab and move around this guy, you will be the first one to regain the crown. You can do it.

Your friend

Archie Moore

Working off his jab, Patterson knocked Johansson out in the fifth round of their rematch the following year.

Moore was someone you wanted to be around,” promoter Don Elbaum remembers. “He was a very classy guy who treated everyone with respect. I sent him a telegram wishing him a happy birthday one year. People did that in those days. And he sent me a telegram back, thanking me.”

Writer W.C. Heinz called Moore “the most scientific fighter of my time and, outside the ropes, the most inventive.”

Al Bernstein recalls, “Archie Moore was the most interesting athlete I’ve ever met. In fact, he was as interesting to sit and talk with in casual conversation as any person I’ve ever known. He had a lot of respect for boxing history and the people who made boxing what it is. He told me once about meeting Jack Johnson in a gym in Los Angeles. He said it was like God walking in. He was a good story-teller but never tried to dominate the conversation. He was self-educated, very well-read. It wasn’t a put-on. He didn’t pretend to be something he wasn’t by throwing out the names of a few writers he’d heard about. There was some double-talk from time to time, but you could discuss anything with him. If he didn’t know about a subject and you did, he’d ask the right questions to learn about it for himself.”

And Larry Merchant, who first encountered Moore as a young sportswriter at the Philadelphia Daily News, reminisces, “I received several long letters from him; letters that went beyond the entreaties for a fight against Marciano or whoever it was he wanted to fight that year. Those letters were one of the things that created a context within which I covered boxing and, to a certain degree, all other sports. He was a man of dignity. He had great pride and grace. Over time, he evolved into a philosopher and, in some respects, an intellectual. Despite all the injustices that were heaped upon him as a black man and as a fighter, he always seemed to be smiling at the world rather than snarling at it. He influenced my life, and I don’t say that lightly. He showed me that writing about sports could be deep and he showed me that writing about sports could be fun.”

“When Archie Moore came around,” John Schulian wrote, “the fight racket never seemed like the sewer it was.”

After Moore died, there were myriad tributes. One of the finest came from George Foreman, who wrote in Time Magazine, “In all the years we talked while Archie was teaching me, he never complained about the years of being the number one contender [when he couldn’t get a title shot]. When he talked of the night he won the light-heavyweight championship but no money, there was that gleam in his eye. When he uttered the word ‘champion,’ that made me too want to be a champion. Archie stands as a tower for all athletes, saying, ‘If you want it, leave your excuses behind and come get it.’”

Thomas Hauser's email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book – The Most Honest Sport: Two More Years Inside Boxing - is available at https://www.amazon.com/Most-Honest-Sport-Inside-Boxing/dp/1955836329/ref=sr_1_1?crid=MLXL6UHY8O9E&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.NZgHyDuy4gb1i6YPJ_9vmAMw3oLJh1d9Sxs-G8xJoJY.67ftevZ4BImTjJoSlE9uPWJz-j5i5wJGtSrlNDVZw-g&dib_tag=se&keywords=the+most+honest+sport+hauser&qid=1750773774&sprefix=the+most+honest+sport+hauser%2Caps%2C65&sr=8-1

In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing's highest honor - induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.