THE SCORECARD / TIGER FLOWERS: THE FIRST BLACK MIDDLEWEIGHT CHAMPION

BOXING HERITAGE

Tiger Flowers: The First Black Middleweight Champion

HOLLY HUMPHREY

He was the finest sportsman and ring warrior I have ever known” - Damon Runyon

Theodore Flowers was born on August 5th, 1895, in Georgia, to the son of two sharecroppers. His early life offered few advantages, but somewhere in that quiet hardship he learned endurance. At fifteen, Theodore left home for Philadelphia and found work in a shipyard. The docks were rough places, men with hard hands and fights were common.

Flowers experienced his first exposure to boxing through informal bouts. Under the guidance of Rufus Cameron, he began fighting in sanctioned matches and soon adopted the name that would define his career, “Tiger”. His first official fight was against a promising young fighter named Billy Hooper. Flowers dismantled him, round after round, leaving Hooper badly injured. His performance caught the eye of Hooper’s manager, Walk Miller, who saw potential in the quiet young man from Georgia. Miller offered Flowers a place in his stable and a job cleaning the gym for fifteen dollars a week. It was modest, but Miller believed in discipline over showmanship. His slogan for his fighters was simple: “Fighters who fight”.

Together, they began a tour of small-town arenas in Kentucky and Ohio, where purses and crowds were small. Flowers wore a black satin robe with a tiger’s head embroidered across the back. It is said that he moved like a panther, and while he was not a stylist, his balance and timing were exceptional.

Flowers was a deeply religious man. He carried a small Bible on his person wherever he went and yet, he never prayed to win.

“I couldn’t pray to the Lord to allow me to win a fight because the good Lord may have made my opponent a better man than me. If I should lose the fight, I’d have trouble with myself to keep from thinking that the Lord had turned me down. I always wait until after the fight and then thank the Lord for seeing me safely through.”

That quiet humility set him apart. He wasn’t loud or flashy. People trusted what they saw, a man who fought with strength and lived with grace.

In the racially divisive era of the early 1920s, Flowers could only fight other Black opponents. Flowers fought whoever would face him, fighting often but learning defeat from boxers such as Kid Norfolk and Sam Langford. When he lost to Lee Anderson in 1922 for the Colored Light Heavyweight Title, he said simply,

“I was beaten by a better man”.

But he learned quickly, requesting that his management match him up with opponents closer to his own weight. The results were immediate, within the next year, he scored decisive wins, including rematches against Lee Anderson. Newspapers began to take notice, blasting headlines with “Tiger Flowers and His Fistic Showers”. By 1924 he had a twenty-one fight win streak.

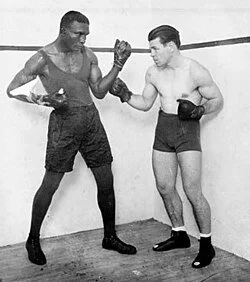

On August 21, 1924, Tiger Flowers fought Harry Greb, the reigning middleweight champion, which saw the beginning of a sporting rivalry between the pair. The fight went ten rounds, with Greb awarded victory by newspaper decision, but the fight made Flowers a name. Even in defeat, his poise won people over.

Stories about his generosity began to circulate. After one particular fight in Mexico City, his train stopped in a poor village where women and children begged outside a bakery. Without hesitation, Flowers walked into a local bakery and spent 25 dollars to feed them all. It was a small gesture, but reflected the generosity of a gentle man.

Two years later, in February 1926, Flowers faced Greb once again for the middleweight title. The fight was close. Flowers took the early rounds. Greb came back strong in the middle. By the twelfth, Greb was exhausted. Flowers outboxed him to the finish. The judges gave him the decision.

Tiger Flowers became the first Black man ever to hold the world middleweight title.

Atlanta erupted. There were parades, speeches and banquets. For a moment, Tiger Flowers was not just a champion, he was a symbol of progress in a country still struggling to recognise the humanity of men like him.

Then came Mickey Walker in Chicago. It was another hard fight. Walker knocked Flowers down twice, once in the first round and once in the ninth. Each time, Flowers rose before the count of ten. He cut Walker’s eye so badly that blood blinded him, but the decision went to Walker. The crowd booed. And yet, Flowers walked across the ring, shook Walker’s hand and congratulated him. The boos swiftly turned to applause.

Flowers never received the rematch he deserved.

Soon after, Flowers began suffering from dizziness and headaches. His right ear was swollen from years of damage and a painful growth had developed over his left eye. His manager, Miller, arranged for a routine operation to remove the growth and reshape the ear. Flowers had shared his unease with Miller, just the year before, Harry Greb had died during a similar procedure. With the memory of Greb still close, Flowers reluctantly agreed to the surgery.

As he lay on the operating table, Bible in hand, he whispered a familiar prayer,

“If I die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take”.

Theodore never regained consciousness.

The anesthetic stopped his heart. He was thirty-two. He left behind a wife and six-year-old daughter in Atlanta.

Walk Miller, was inconsolable. The two had struggled together, prospered together and had become more like brothers than business partners. Nine months later, Miller was found dead, a bullet through his head and heart. The coroner ruled it a suicide.

“Tiger Flowers was a credit to his calling”, one reporter wrote. Another, “The greatest barnstorming fighter that ever lived will travel no more”.

Tiger Flowers’ career was brief, his life shorter still, yet his name remains one of boxing’s most fitting paradoxes - Tiger Flowers, a man of ferocity and faith. In the violence of the ring, he found a kind of grace. And in an age when dignity was often denied to men of his colour, he carried himself with the quiet conviction of someone who understood both the limits and possibilities of the world he lived in. He fought within the ropes, but his example reached well beyond them.